By daybreak we could see our destination (Okinawa Islands) 300 miles from the Japanese mainland. We refueled, took on water, and was anchored in the early afternoon. 0400 general quarters sounded Japanese air attacks. This lasted off and on until the full of dawn. Again at dusk GQ sounded. Things were pretty hot for a while.

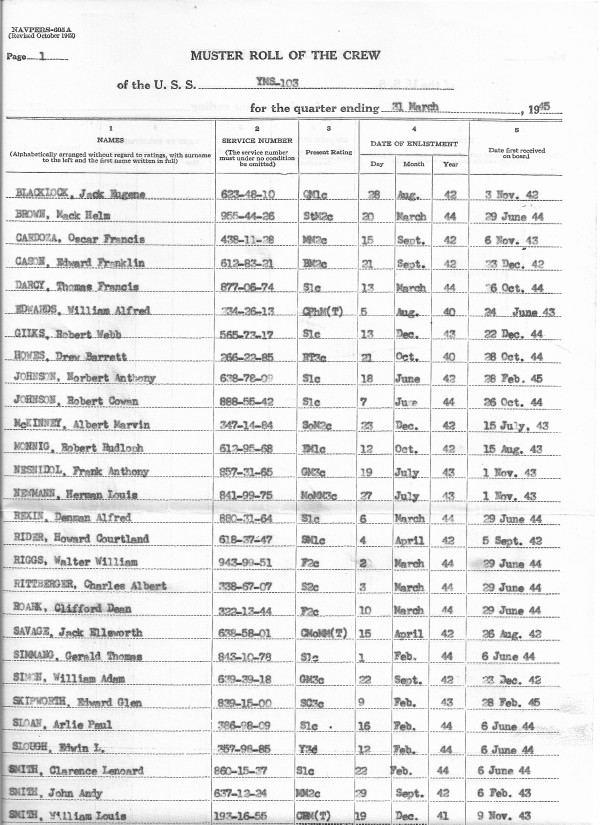

Also via Richard Thornton, this is the first page of the YMS-103 muster roll. I don’t have the equivalent of this for YMS-299 yet, though I was curious what the document looked like.

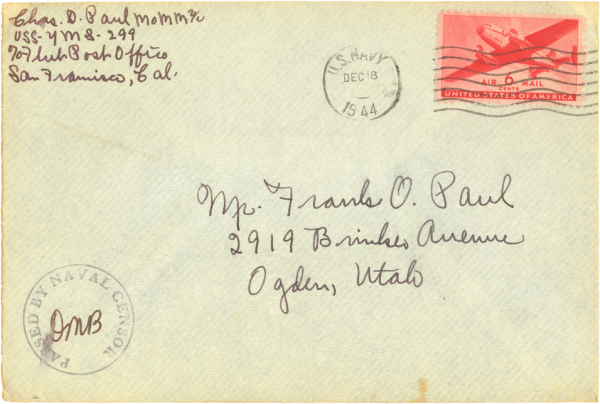

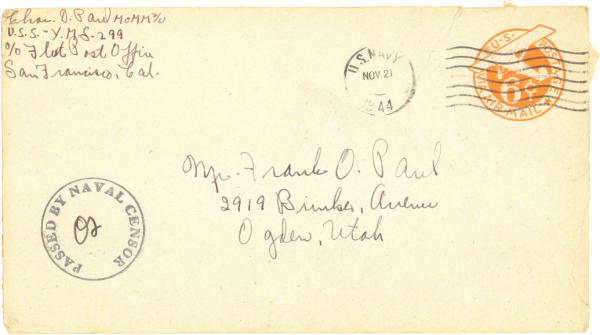

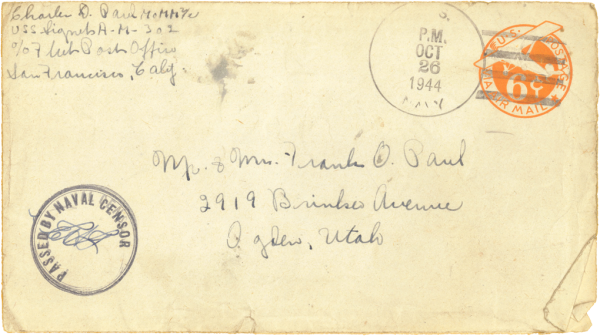

Envelope (front); December 5, 1944

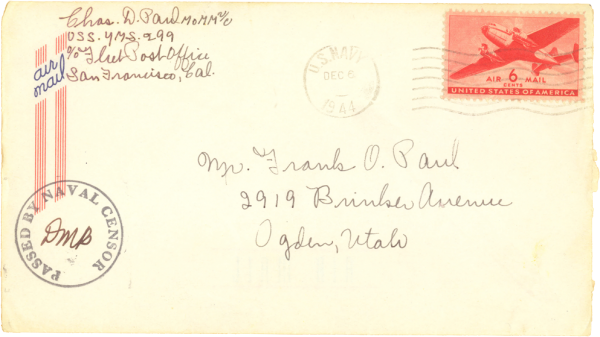

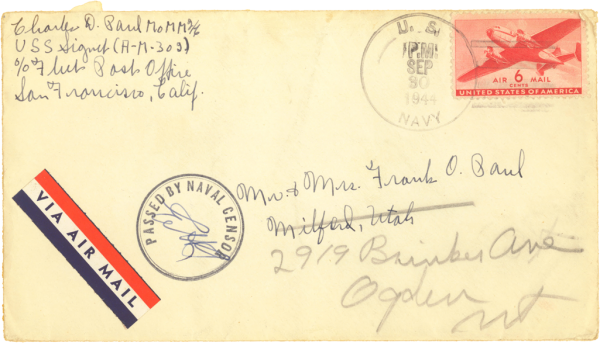

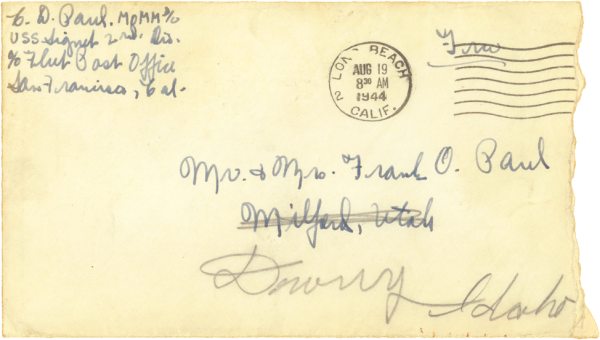

Envelope (front); November 19, 1944

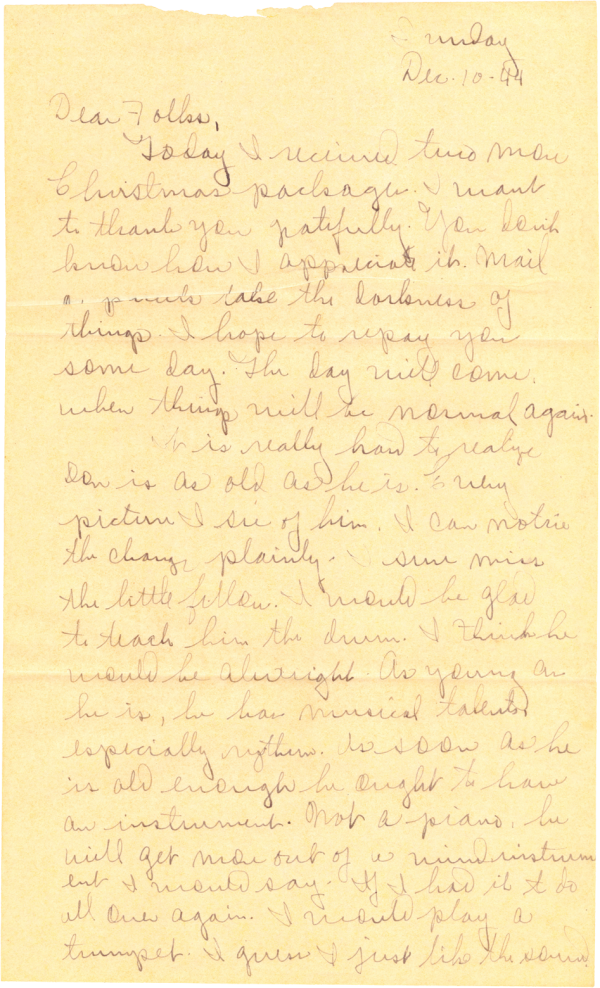

Well, this is exciting! This is the first letter postmarked from the YMS-299.

The stomach problems have returned, that are presumably a mixture of butterflies for war and seasickness. He is tired of water and yearning for the land in back in Utah.

Ending this letter, he talks about laundry by brush. They never did get a washing machine. There isn’t room for it on such a small ship. I have an audio interview that I’ll post when I can, where he discusses the process and humor in laundry. They would tow their clothes on a line in the water to wash them, then lay them out to dry. They collected so much salt in them that they would become stiff and crispy, making velcro-like sounds when you moved in a freshly “cleaned” pair.

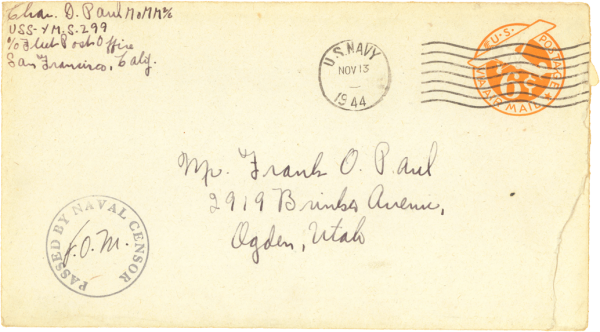

Envelope (front); November 12, 1944

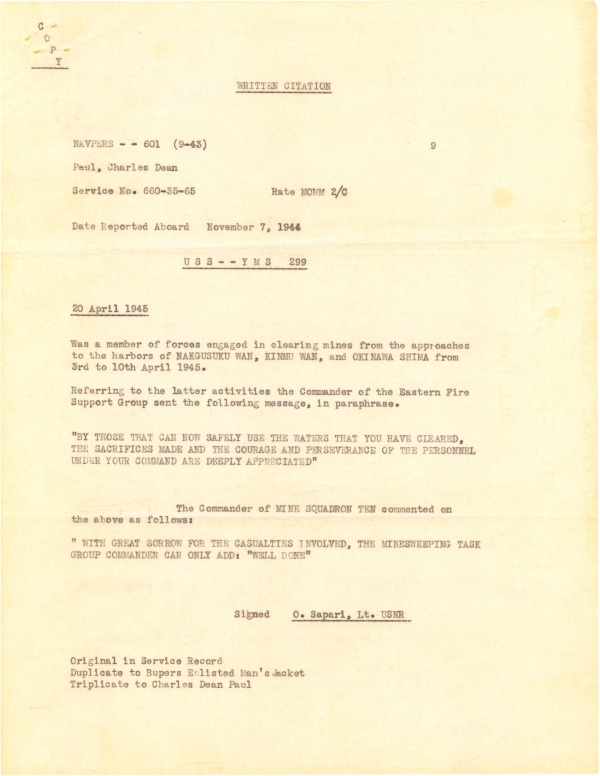

This is the citation mentioned in Chuck’s September letter home, commending the troops for their efforts in kicking off Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa during early April, 1945. This letter was given to all members of the YMS-299 crew (I have a second copy of it addressed to Thomas Morley, sent to me by his son).

042045 Written Citation

Chuck mentions news about “the islands” that he is in. I am assuming he is referring to Hawaii, as he hasn’t shipped to the war yet and the post office is still in California.

The ship he is referring to likely wouldn’t be his own ship, but the USS Signet (AM-302). The Signet is, I believe, the transport ship he is going to take into the war. I’m guessing the crew and supplies on the YMS itself would need to be as trim as possible to make the long journey quickly and with fuel efficiency.

Envelope (front); November 6, 1944

This letter has one of my favorite bits of artwork of all of his stationery. The disc behind the hula girl is a tropical scene a bit hard to make out. The right is a trunk of a palm tree, with some leaves coming from the top. I am not sure what is in her hands, but I’m guessing it is some sort of rattle/instrument. It appears to be made of coconut shells.

Stationery artwork; October 24, 1944

He mentions some love interests. Neither are anyone he ever married, so I don’t have backstory on them.

Also interesting, he acknowledges that he is not allowed to keep a wartime journal. This was common on both sides because picking journals off of the enemy could give intelligence on movements and strategy. Of course, he kept a journal anyway. Keeping a journal would have been a religious conviction (Mormons are urged to keep journals for posterity), but it is out of character for Chuck to break the rules, so I’d be curious what swayed his decision to keep the journal anyway.

Envelope (front); October 24, 1944

Note the “see code” reference. It looks like Frank’s handwriting. Again, I haven’t attempted decoding any of the letters yet.

In this letter, Chuck is already thinking about what he wants to do after the war he hasn’t even been in yet. He mentions drumming. Playing in a jazz band was something he enjoyed through his life, actually playing weekly until his death in his 80s. He never worked on rail, as he mentions. I’m not sure what he did immediately post-war, but the bulk of the work he talked about was at the Coors canning plant.

Envelope (front); September 27, 1944

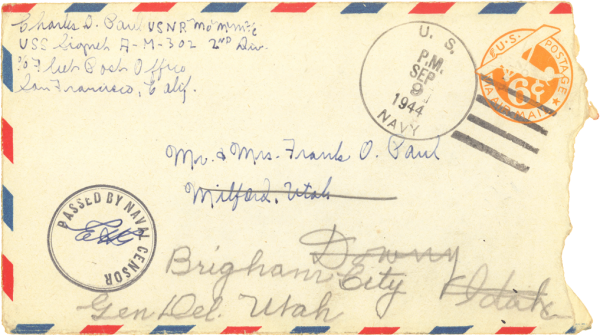

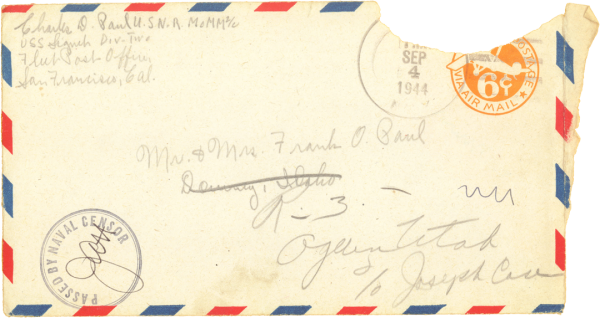

It is peculiar how the postal system worked at this time. There are several addresses crossed out and rewritten, along with the associated stamps that let you know the envelope actually went through each of these relays before making it to their recipient.

There are some fun terms in this letter as well. I translated “cow’s age” but didn’t find any definition online for it. Both “cow’s age” and “crow’s age” seem to be used in extreme rarity and I couldn’t figure out a better translation, thinking it possible that neither of those is what is written. If you know it is another saying, please let me know. Otherwise, it sure looks like “cow’s age”.

“Fishful” is another odd term, meaning something is abounding with fish and usually used as an adjective. CDP uses it as a noun in this situation, meaning he is taking some liberties with the word and using it as a measurement for a lot.

Keep in mind CDP was as close to a farm boy as you can be, without actually working on a farm. His family was in the West, where much of the area was still pretty close to wild, even in the last century. Idaho and Utah, even now, are not dominantly suburban. His letters and journal are littered with misspellings for words we might find mundane. One that keep tricking me is his use of “kneed”, actually being “need”…presumably hyper-correcting for “know”.

In addition to mundane words, when we get into the journal and the later war letters, all of the military terminologies and names of Japanese locales are spelled incorrectly. This was commonplace amongst soldiers, many of whom knew nothing of the Orient prior to being shipped out. Due to secrecy of the situation, soldiers would likely have never seen the names of targets or military terms written or printed on anything, left solely to translate phonetically.

You can see the censor has been tightening down. There are multiple references in this letter to wanting to say more, but being bound not to.

Envelope (front); September 8, 1944

Chuck mentions his code in this letter, somewhat conspicuously even though it was going through the censor. I’m having trouble figuring out his decoder from the previous letter, so I haven’t tried to pull out the hidden message yet.

The “fantail” is a an extension off the back of aircraft-carrying ships that extended the runway for takeoff and landing. The runway on landing ships was just long enough for takeoff, with planes usually dipping before rising as they fell off of the fantail. Inversely, in landing, there was an “arrester” that caught planes (rather abruptly and non-gracefully from accounts I’ve read) before they wrecked into anything else on the deck. Landing was particularly dangerous in night sorties, as turning runway lights on left the ship vulnerable to the enemy ships. Pilots would have to land in the dark, leading to a high volume of wrecked planes. Fortunately, the US was mass producing planes in such force by 1944 that when they became damaged or corroded from the salty air, they would simply get pushed overboard and written off. The flyboys were accustomed to making sea “landings” near their ship, with their cockpit locked open so they wouldn’t get sucked down and could be picked up.

Chuck laments his drumming. Chuck was an avid drummer from his youth up until his death in his 80’s. His favorite music was ballroom jazz and naturally Hawaiian music. Into old age, he played in a senior band every weekend. A sense of percussion runs in the family. My father drummed the steering wheel and I do the same, often making up my own counter rhythm to songs…despite never doing anything significantly musical. I could see how, if I had, I’d have naturally followed in Chuck’s path.

I’m not sure what he means by making his “rate”. Obviously it is a pay rate of some kind, but from the envelope it doesn’t look like his rank has changed since the last letters.

I’m not sure what is going on with the photo from home. He has been requesting it in several letters, obviously not having received it yet. I have a handful of photos of the family from this time period, so it isn’t that one didn’t exist. I wonder if perhaps he was simply not receiving many letters from home. I do not have the reciprocated letters in this dialogue.

Letter home, envelope (front); September 3, 1944

Letter Home, August 18, 1944

Aug 18

In this letter, Chuck is still waiting to hear when and where he’ll be going. However, he has been getting exposure to the ship and practicing his shooting.

He mentions being in charge of a “kay gun”. A K-gun is not really a gun at all, but a depth charge launcher. The model on this ship would likely have been a Mark 6, introduced in 1941 and used through the end of the war. The K-gun projector would launch an underwater charge with a distance of 60 to 150 yards with impact in less than 5 seconds. Depth charges were used on as anti-submarine warfare. They were not required to come into contact with the submarine, as the shock of the explosion under water was usually enough to put them out of commission.

On Wikipedia: Depth Charge

Letter home, envelope (front); August 18, 1944

Letter Home, June 29, 1944

Jun 29

This is the first letter where Chuck starts talking about his ship assignment. He talks about loading up supplies, the upcoming shakedown and starts wondering what his mission will be. (There is a word I couldn’t discern from the handwriting. If you can tell what it says, please comment.)

A shakedown is a new ship’s initiation, prior to setting into the open sea. A ship is put through stress tests and drills to make sure it is seaworthy. The tests are both for the integrity of the ship itself and its crew, who is often being freshly introduced to the ship and its capabilities.

Also interesting in this letter is Chuck’s “code”. He has come up with a system of passing messages to his family to bypass the censors. I haven’t gotten into the latter letters yet, to see if he ended up using it or not. We’ll see!

The reply at the end of the letter is Frank O. Paul, signed “FO.” I’m not sure when he would have written on the letter, or why, as I am sure he wouldn’t have been mailing the letter itself back to Chuck. Also regarding his note, I think I’ve read it correctly despite the sentence being incoherent. If you are able to read it as something that is more logical, please let me know.